The Fractal Generator

This research project was an optional part of the MATH326 - Nonlinear Dynamics & Chaos course offered by McGill during the Fall 2021 semester.

Built using Python, HTML and CSS, our Fractal Generator web application includes the following fractal generating functionalities:

1. Chaos Game

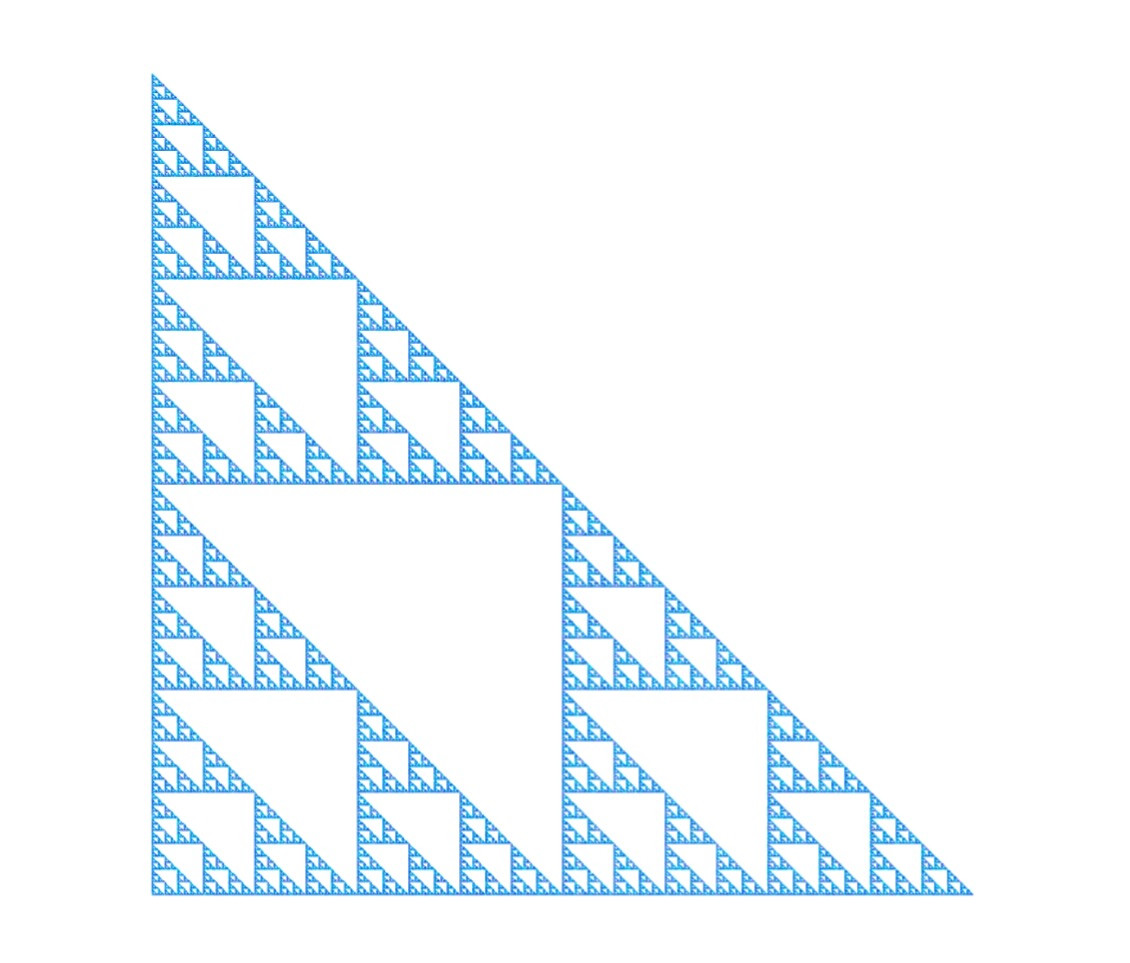

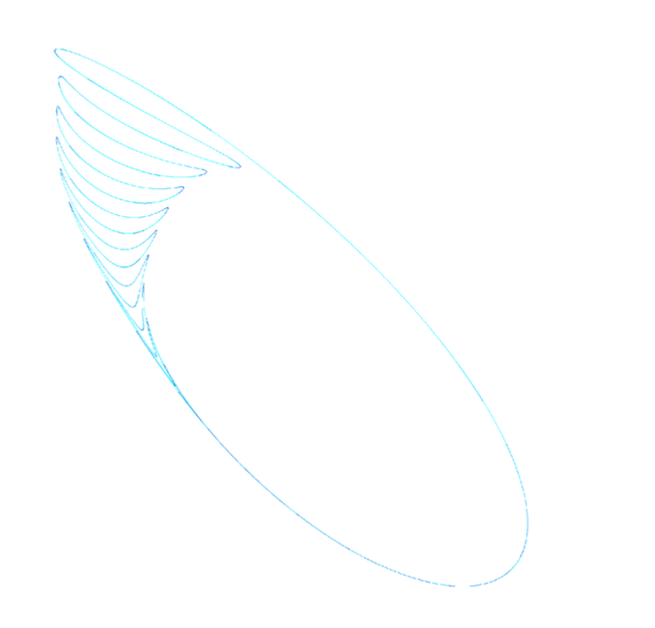

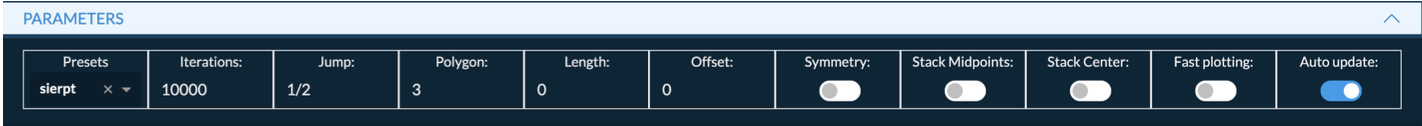

Fractals such as the sierpinski triangle and the viscek square can be drawn using the chaos game feature. The user can choose the initial polygon, specify the compression ratio of each iteration, and incorporate extra rules to form a variety of attractors.

2. General Iterated Function Systems

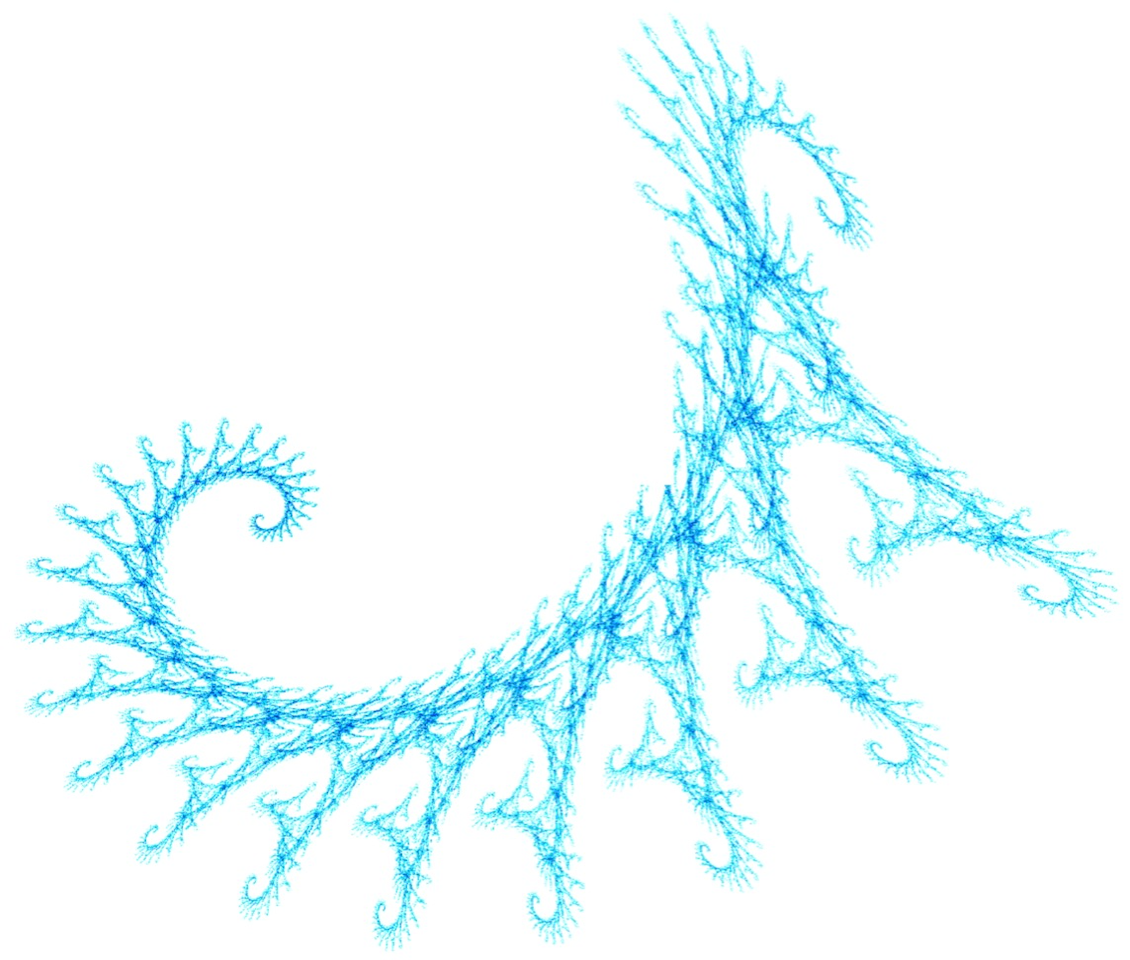

The application incorporates the more general concept of iterated function systems (IFSs), with which even more complex fractals can be constructed, wherein the user specifies a list of possible transformation parameters and their relative weights.

3. Chaotic Discrete Map Generator

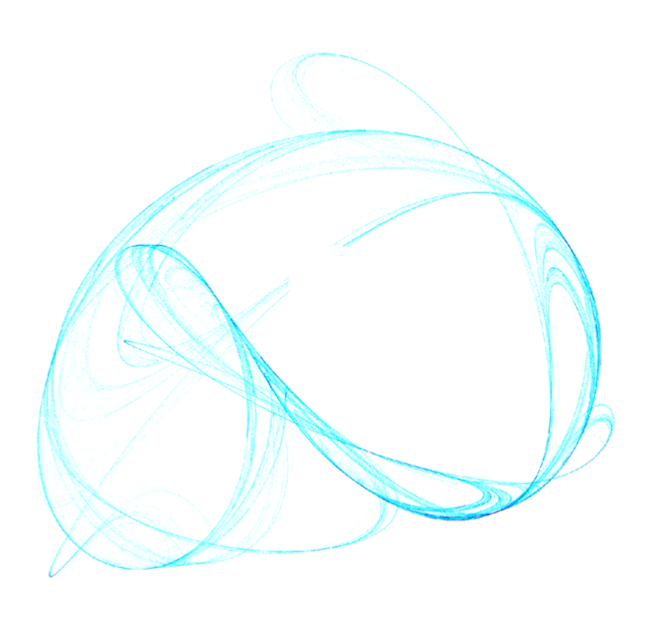

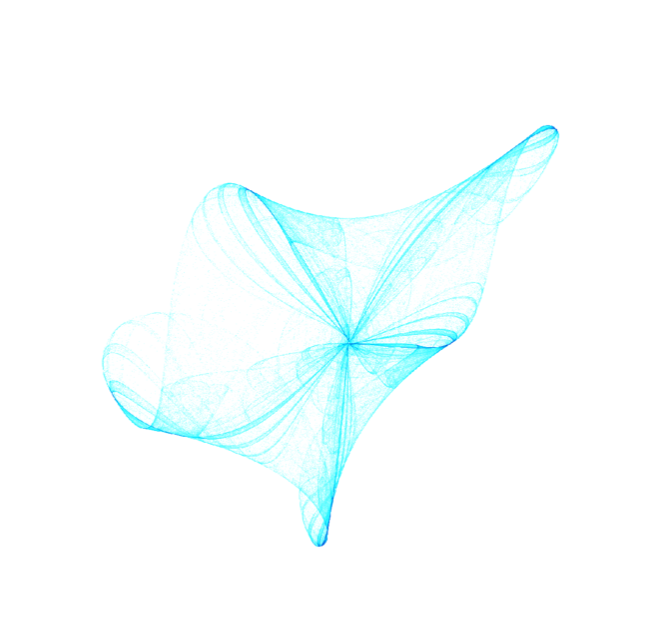

The application has the feature to iteratively find 2D chaotic discrete maps which often yield beautiful fractal shapes when plotted.

Iterated Function System & Chaos Game

An Iterated Function System (IFS) is a finite set of contractive functions which are applied iteratively on an initial point ad infinitum. At every iteration, one transformation among the set is chosen at random and applied to the previous point, yielding the next input for the next iteration.

The chaos game is an example of an IFS. In brief, the classical version consists of choosing a random point within an equilateral triangle and repeatedly applying the following procedure:

- Randomly choose one of the vertices of the triangle

- Jump half-way from the previous point to the chosen vertex

- Repeat with the newly drawn point

The game can formally be defined as an IFS with the following three choices of transformations:

$(x_{n+1}, y_{n+1}) = (0.5\,x_n, 0.5\,y_n)$

$(x_{n+1}, y_{n+1}) = (0.5\,x_n + 0.5, 0.5\,y_n)$

$(x_{n+1}, y_{n+1}) = (0.5\,x_n, 0.5\,y_n + 0.5)$

After a sufficient number of iterations of these transformations, and with initial conditions within the triangle, the Sierpinski right triangle is generated. This is a surprising result given that the transformations are chosen at random. The system consistently forms the same fractal attractor!

Automatic Generation of Discrete Chaotic Attractors

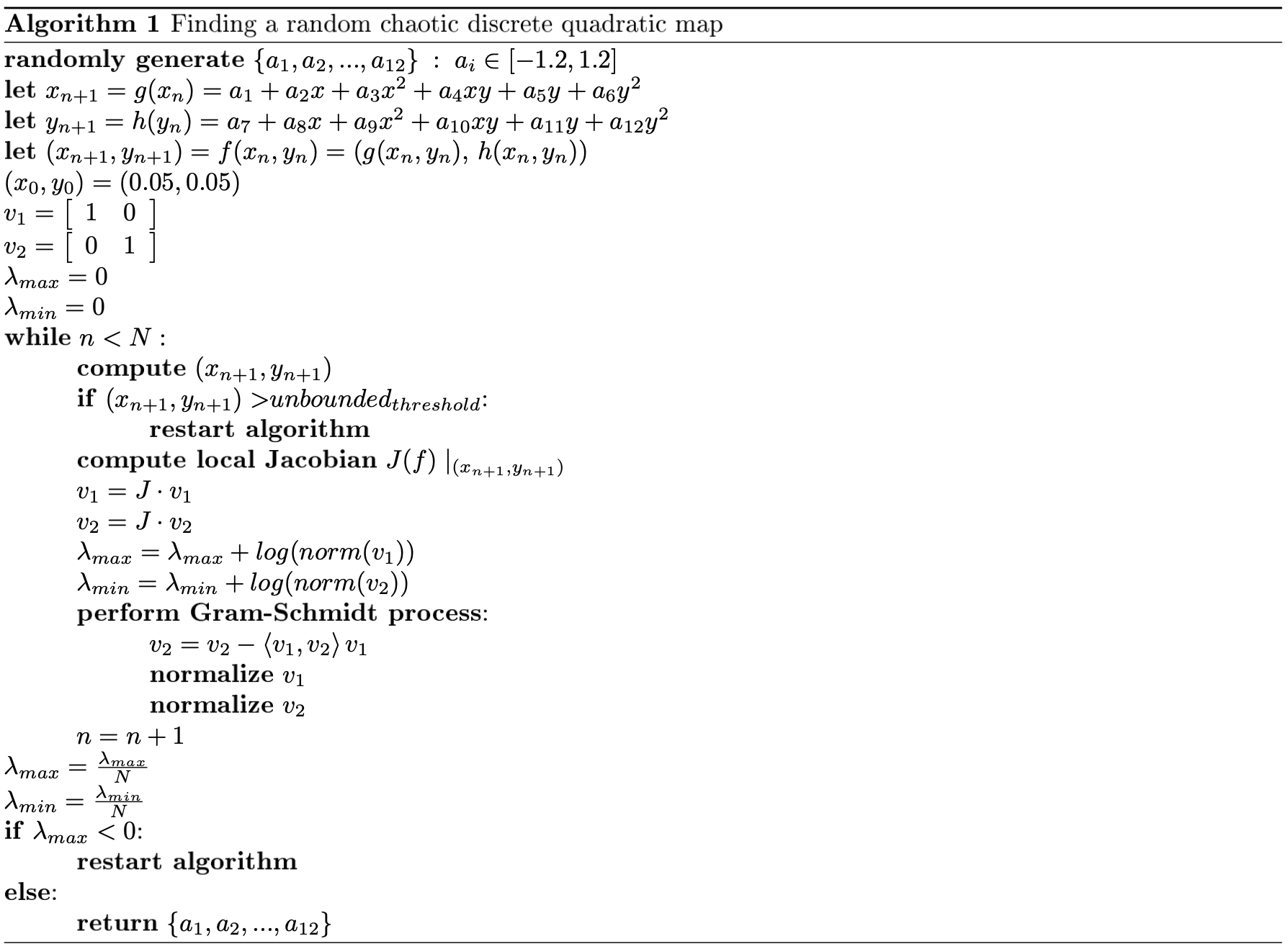

1D discrete maps can exhibit chaotic behaviour if their lyapunov exponent is positive. Similarly, 2D discrete maps exhibit chaotic behaviour if one of their lyapunov exponents is positive. Our website includes a feature which automatically finds quadratic and cubic chaotic 2D maps.

Finding such maps consists of first generating a random map and calculating its lyapunov exponents. If one of them is positive and the map is bounded, it is chaotic. Otherwise, the process is repeated until the conditions are satisfied.

Similar to the pull-back algorithm, this process is analogous to the classical computation of the lyapunov exponents of a map. The displacement vectors are orthogonalized after each iteration to align with the corresponding eigendirections, and normalized to prevent computational overflow.